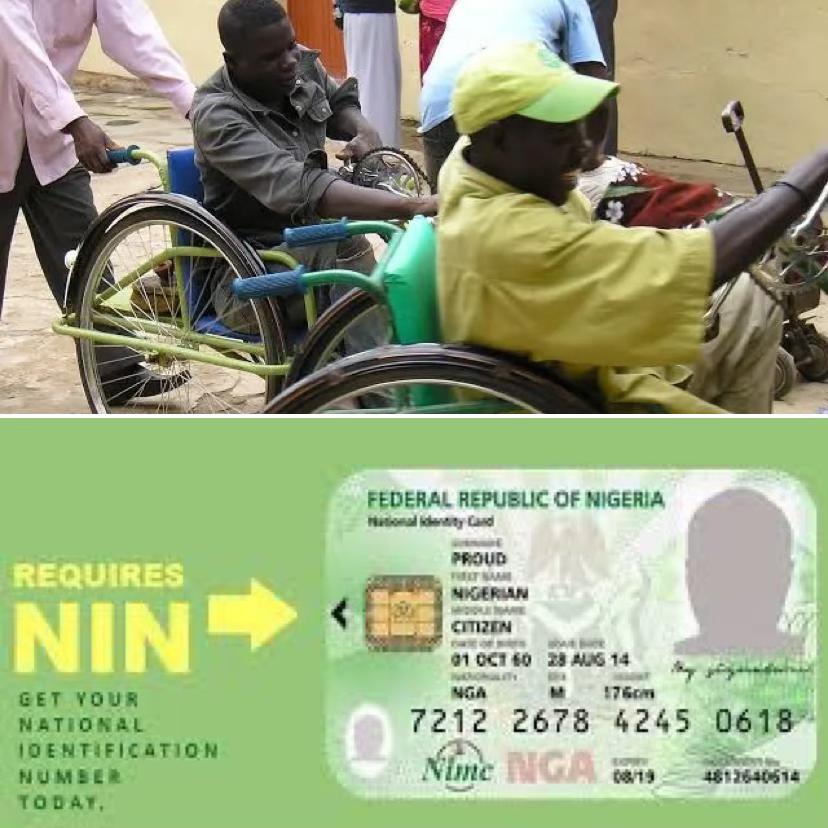

In the heart of Nigeria, a country where millions rely on the National Identity Number (NIN) to access vital services, a particular group of citizens face an ongoing, invisible battle: persons living with disabilities. For many, securing a National identification number NIN is not a simple task—it is a struggle that highlights the systemic barriers and social exclusion faced by one of the most marginalized groups in the country.

A Day at the Registration Center: A Story of Frustration

When Iyanuoluwa Akinbode, a 40-year-old woman living with cerebral palsy, arrived at the National Identity Management Commission office in Akure, Ondo State, on the 27th October 2022 she had no idea how difficult her journey would be.

“I was excited about finally getting my National identity number NIN,” she said, her voice tinged with frustration. “It’s something everyone tells you to have, something everyone else has. But for me, it has felt like an endless uphill battle.” She said Iyanu, who uses a wheelchair, was quickly confronted with a series of physical barriers as soon as she entered the center. The building had no ramps or accessible entry points, forcing her to be carried inside. Once there, she was told she needed to provide her thumbprint for her application. A simple task for most, but for her, it became an impossible hurdle.

“As someone without hands and fingers, it has always been an incredibly frustrating and humiliating experience, and now being asked for a thumbprint feels very awkward. I feel like the system doesn’t even consider my situation.”

“I gave a bad stare at the officer asking for a thumbprint like, can’t this guy see that I can’t provide a thumbprint because I don’t have fingers, I was met with confusion as No one had any real solution or alternative for me. I was told to come back later, as if they were just passing the problem on.” Iyanu vented.

She continued, “It’s not just about the thumbprint. It’s about the assumptions people make about us. When I went to the center, the staff didn’t seem to understand that my disability doesn’t mean I am incapable. I felt like I was being treated as an afterthought—like my needs were too complicated to accommodate.”

“I had to explain several times that I can’t use my hands for basic tasks, but that I am still a person with rights, including the right to identification. They looked at me as if I were asking for something extraordinary, when all I wanted was to be treated like any other Nigerian citizen.”

“Finally, after much persistence, I was told they might be able to use other means to register me, that an official will have to take a picture with me and also show that i am disabled and can’t thumb print. That was after a lot of back and forth” Iyanu continues.

“I hope that in the future, there will be more thought put into the process,” said Iyanu. “There’s a need for inclusivity, to help us feel like we belong, like we matter.”

“If the process could be moved online, or if there were digital alternatives to thumbprints, that would make it so much easier. I would not have to deal with the physical limitations of the center. I could do it in the comfort of my home, and I wouldn’t need to explain myself over and over again.”

She added that, “I believe embracing digital technology could solve the problem of fingerprinting. “If they could use facial recognition or some other method to register us, it would be so much better. It would be fairer for everyone, and it would give people like me a real chance to be recognized as part of society.”

“It’s about being seen, being heard, and having a fair chance to access the same rights as everyone else. Digital infrastructure can make that happen, but only if the government makes the effort to include us.” She emphasized.

NIMC’s Commitment to Inclusivity

Dr. Alvan Ikoku, focal person for the National Identity Management Commission NIMC, while speaking to the Media foundation for West Africa MFWA DPI Journalism Fellows during a training in Abuja expressed his concern regarding the barriers faced by persons with disabilities during the NIN registration process. “We are fully aware that the current registration system presents significant challenges for persons with disabilities,” he said. “Our priority is to ensure that every Nigerian, regardless of their physical condition, has access to the services they need. The situation we currently have, where many persons with disabilities are unable to complete the process, is unacceptable.”

He explained that the issues stem not only from physical barriers at the registration centers but also from the reliance on fingerprinting as the primary identification method. “The fingerprinting requirement, which is essential for verifying identities, is difficult or impossible for some people with disabilities,” he said.

In response to the growing concerns, NIMC has begun making efforts to improve accessibility at registration centers. “We are actively working to ensure that our centers are more physically accessible to persons with mobility challenges. This includes the installation of ramps, wider doorways, and more accessible facilities,” He confirmed. “We know this is just a start, and we plan to continue improving the physical infrastructure across the country.”

Additionally, NIMC is exploring ways to incorporate alternative forms of identification, such as voice recognition, retina scanners and facial recognition technology. “We are in discussions with technology experts to explore alternatives to fingerprinting, particularly for those who cannot provide a thumbprint due to their disabilities,” said Dr. Ikoku. “There are innovative digital solutions that can help make the registration process more inclusive, and we are committed to integrating these solutions into our system.” He also emphasized that embracing digital public infrastructure could play a pivotal role in resolving many of the barriers faced by persons with disabilities. “Digital transformation is key to addressing these challenges. With the right tools, we can ensure that Nigerians with disabilities are not left behind,” he explained. “We are looking into advanced biometric systems that go beyond traditional fingerprinting.

Experts Opinion: The Need for Digital Public Infrastructure

“Globally, it is estimated that 15% of the population lives with some form of disability, according to the WHO’s 2011 World Disability Report. In Nigeria, this translates to a staggering 25 million people, who, despite comprising a significant portion of the population, face serious barriers in accessing essential services, including healthcare, education, housing, and government documentation.”

Experts believe that embracing digital public infrastructure could be key to solving the accessibility issues faced by persons with disabilities in Nigeria.Digital public infrastructure has the potential to revolutionize how persons with disabilities interact with the government. With the right systems in place, the process of securing a NIN could be more accessible and inclusive. Digitalization also offers a way to reduce the frustration and delays caused by in-person registration processes. With an online system that considers the diverse needs of people with disabilities, registration could be more streamlined, eliminating the need for multiple visits to centers.

According to Precious Ibeh, a disability rights advocate, the current NIN system fails to recognize the specific needs of persons with disabilities. “The rigid process of thumbprinting simply does not work for everyone. We are in a digital age, and there are alternatives—such as facial recognition, voice identification, or iris scanning—that could replace the need for fingerprints,” she said. “The government must consider these alternatives if they are serious about making services accessible to everyone, including people with disabilities.”

Ibeh added, “Persons with disabilities in Nigeria are often treated as second-class citizens, not because of their abilities, but because the systems in place are not designed with them in mind. The NIN process is just one example of how this exclusion manifests.”

An IT expert Mark Kuti said “The future of Nigeria’s public services lies in the digital transformation of government systems, but that future needs to be inclusive. Digital platforms should be built with accessibility in mind, especially for marginalized groups such as persons with disabilities.”

He further stressed the importance of moving beyond the traditional identification methods. “Digital infrastructure can help move away from outdated practices like thumbprinting, which are exclusionary. The use of biometric data, such as facial recognition, or voice recognition systems, could make identification easier for people who cannot physically provide a fingerprint.”

Kuti also highlighted the broader impact of digital inclusion. “Incorporating accessible digital systems into the NIN registration process would not only ensure people with disabilities have equal access, but it would also streamline the process for everyone, improving efficiency across the board.”

Advocacy Responsibility: Ensuring Equal Access

According to a human right lawyer Valentine Agabi digital public services must be designed with inclusivity in mind. “It’s time for policymakers to create systems that acknowledge the diversity of the Nigerian population, including the various types of disabilities people live with.”

Agabi argued that the National ID registration process, like many other government services, must undergo a major overhaul to ensure no one is left behind as people living with disability have the same rights as other citizens which shouldn’t be trampled upon. “Digital infrastructure is the way forward, but it needs to be properly adapted to ensure that people with disabilities are not left out,” he said. “We are living in a world where technology can offer solutions to many of these challenges, but the government must take responsibility and ensure that its systems are not only functional but accessible to all.”

As Nigeria continues to modernize its public services, experts agree that making the NIN system more accessible through digital infrastructure is an essential step toward creating a more inclusive society. If the government can prioritize accessibility and incorporate digital solutions that cater to people with disabilities, the future of identity verification could become a much smoother, more equitable experience for all citizens.

For now though, the battle continues for persons like Iyanuoluwa and other individuals who are fighting not just for a NIN, but for recognition as equal citizens in their own country.