Raliat, a 34-year-old housewife from Farin Shinge, Niger State, does not have a National Identification Number (NIN). To enroll, she would need to travel to the registration centre in Kontagora, a journey her husband refuses to fund. Without it, Raliat cannot access maternal healthcare tied to Nigeria’s Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF), which requires NIN verification.

“I know there is free healthcare for mothers,” she says. “But without a NIN, I cannot enjoy it.”

This exclusion appears to be a pattern. Raliat’s experience is not an isolated case but a systemic failure in Nigeria’s Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI). Digital identity is the foundational layer of DPI, enabling access to payments, social protection, healthcare, education, and civic participation. When women are excluded from this layer, they are effectively locked out of the entire digital ecosystem.

In Niger State, more men have digital identities (IDs) than women, but not because women do not need them. As of June 2025, only 38.8% of enrolled NIN holders are women, compared to 61.1% men. This 22.3% gap is a barrier to women’s access to mobile banking, education, and political representation. Without digital recognition, women like Raliat are excluded from the country’s data, absent from policy debates and economic planning. Here, patriarchy and crumbling infrastructure conspire to deny visibility, ingraining cycles of poverty and dependency.

When Patriarchy Meets Broken Infrastructure

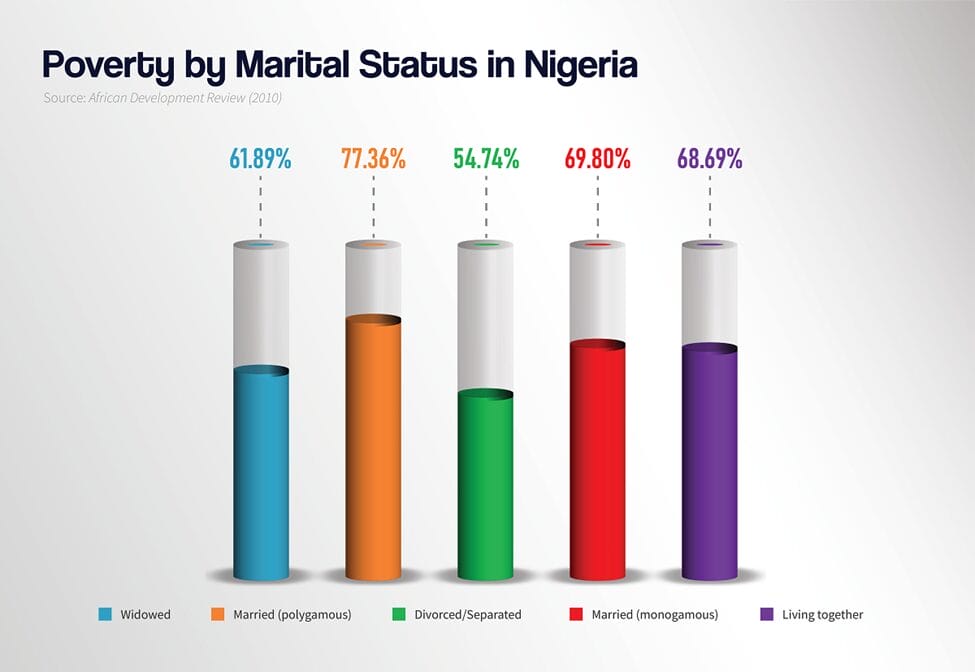

Women in Nigeria face systemic barriers to identity registration, including lower income, limited education, and restricted mobility, as highlighted in a survey on Marital Status and Poverty. The study reveals that larger household sizes and traditional gender roles disproportionately trap women in poverty. Rural women shoulder endless domestic duties while being denied NIN services, deepening exclusion.

In Rijiya Nagwamatse, 38-year-old farmer Amina, mother of eight, has never travelled outside the village. “The ID office is in Kontagora,” explains her husband, Saidu, who is unemployed. “Without a family member, my wife cannot go alone.”

Similar sentiments are recorded across many rural areas in the state. In Ibeto, 40 km from Kontagora, 18‑year‑old secondary‑school student Zainab attempted to register for NIN in 2025. Even after securing her father’s consent, “the N3,000 transportation to and from the registration centre cost more than his weekly income,” she says. “I have given up. Why should I even bother? What’s the point of getting it anyway?”

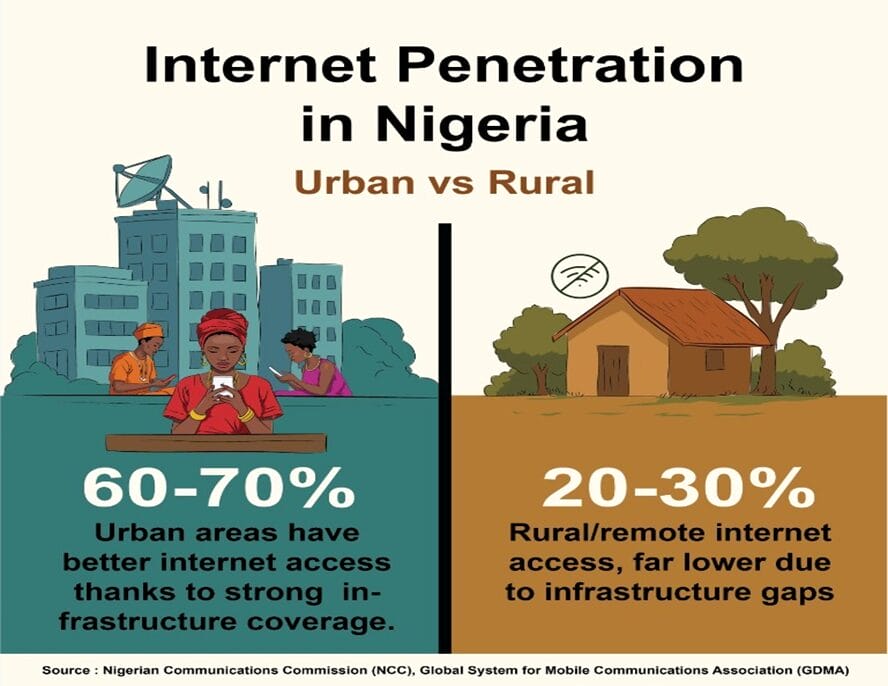

Her experience reflects a sad reality where 78% of urban women own phones, but only 42% in rural areas do. Men, meanwhile, far outpace women in mobile phone ownership with 73% vs. 58% in semi-urban centres.

Structural gaps in DPI compound the issue. A World Bank report estimates that only 20% of rural villages have internet access, limiting the reach of NIN-enabled financial services such as digital payments, credit, loans, and pensions. The National Identity Management Commission (NIMC) has concentrated enrollment infrastructure in urban centres, leaving rural women at the margins of the identity ecosystem.

Yet exclusion is not purely infrastructural; it is also ideological. Uthman, another resident of Rijiya Nagwamatse, argues, “Women here are protected. Let them stay with their families. Who will cook for the children if a mother leaves the home?”

His wife, Hauwa, however, counters, “He has his NIN. But when I ask him to let me get mine, he says, ‘You are a woman. You already have food’.”

The DPI Cost of Exclusion

In a DPI-enabled state, digital identity is the gateway to financial inclusion, service delivery, and legal recognition. For women in rural Niger State, exclusion from this gateway has cascading consequences. Without digital identity, access to essential services offered by governments and the private sector plummets. In Nigeria, 25 million adult women lack bank accounts, while over 16 million in rural areas rely solely on unstable informal financial systems.

Women’s World Banking identified a link between access to digital identity and financial inclusion for women. It was noted that as ID ownership increases, so does access to economic opportunities. But the toll of exclusion on women is more than just financial.

Beyond finance, exclusion from digital identity undermines access to essential public services. In Niger State’s Primary Healthcare Centres, for instance, mothers without a NIN are denied the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF), depriving them of free maternal care.

A digital ID unlocks economic opportunities, legal recognition, and access to essential services. For rural women, it is the foundation for empowerment, security, and equitable participation in society. Bridging this identity gap is both a technological and moral imperative.

State Efforts and Structural Shortcomings

In 2025, in line with the NIMC Act No. 23 of 2007, the Niger State government launched an initiative integrating the NIN into the Social Safety Register. This move was aimed at enhancing identity verification, ensuring data accuracy, and improving interventions for poor and vulnerable populations, particularly women in rural communities.

Mrs. Funmi Olotu, National Coordinator of the National Social Safety Nets Coordinating Office (NASSCO), affirmed the importance of accurate identity data. “The use of NIMC registration devices for accurate data capture will ensure that social intervention reaches those who need it most.”

However, these efforts have been limited by scale, access, and awareness. At Tudun Wada PHC, Nurse-in-Charge Eigboche Bernice Ibrahim confirmed that only one NIN registration outreach occurred in 2024. Long queues and logistical challenges deterred many.

“I left the queue because my customers were waiting,” shared 54-year-old trader Fatima Lawal, one of countless rural women still without NIN.

According to NIMC Director-General Mr. Aliyu Aziz, a joint NIMC-World Bank gender study identified key barriers such as low awareness, perceived lack of ID value, limited access, time constraints, insufficient documentation, and biometric capture issues.

With only 21 NIN centres for a population of 7.5 million residents, the system is ill-equipped to enroll Niger State’s 3,850,000 women at scale. Also, urban-focused campaigns often miss rural realities, where myths persist that NIN is “for city people” or that fees apply, despite free enrollment.

Building Gender-Responsive Digital Public Infrastructure

Closing Niger State’s digital gender gap requires intentional, gender-responsive DPI design. Digital identity systems must be built not only for scale but also for inclusion, especially for populations constrained by mobility, poverty, and social norms.

Decentralised, offline-capable ID enrollment models, such as those piloted in Ogun State, can reduce rural women’s travel burdens by enabling village-level enrollment. Strategic partnerships with women’s cooperatives and faith-based groups can also extend reach through trusted community networks.

That said, cultural barriers demand equally innovative solutions. “There should be ‘male ally’ programmes, where husbands, community stakeholders, and religious leaders are encouraged to allow women own a digital identity, says Halima Musa, a community facilitator at Youths in Justice Health & Sustainable Social Inclusion (YIJHSSI).

It’s not about forcing men to support us,” she explains. “It is about showing them that when women succeed, the whole community does.”

The Road to Inclusive DPI

The digital divide displaces many rural women in Niger State from public identity systems, threatening their participation in economic and civic life. For every woman denied a NIN, an identity, and a future is lost. This exclusion risks decelerating progress in a state where women’s contributions are the backbone of farming activities and agribusinesses.

Expanding mobile NIMC registration units and deploying biometric kiosks in high-traffic marketplaces, where women gather daily, can bridge logistical gaps. State leaders could also integrate gender parity metrics into enrollment targets, prioritizing inclusivity as a core governance indicator. Meanwhile, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) must raise awareness through radio jingles, indigenous storytelling, and local media to normalize women’s engagement with digital systems.

The economic case is compelling. The World Bank has found that closing gender gaps could raise GDP by as much as 12% in low-and-middle-income countries like Nigeria. For Niger State, the stakes are even higher.

As Musa puts it, “Until women in rural Niger are included in the digital fold, our growth remains slow. But if we let women in, we unlock not just their potential but the State’s.”

This report is produced under the DPI Africa Journalism Fellowship Programme of the Media Foundation for West Africa and Co-Develop.