Lagos, Nigeria’s commercial hub, is Africa’s second-largest city economy after Cairo, with an estimated population of over 22 million people and a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of about $259 billion based on Purchasing Power Parity (PPP).

Yet, beneath this economic scale lies a persistent access gap. For many residents, especially in peri-urban and fast-growing communities, formal banking services remain distant, congested, or costly. Some are unbanked; others are banked but discouraged by long queues, transport expenses, and time lost in banking halls.

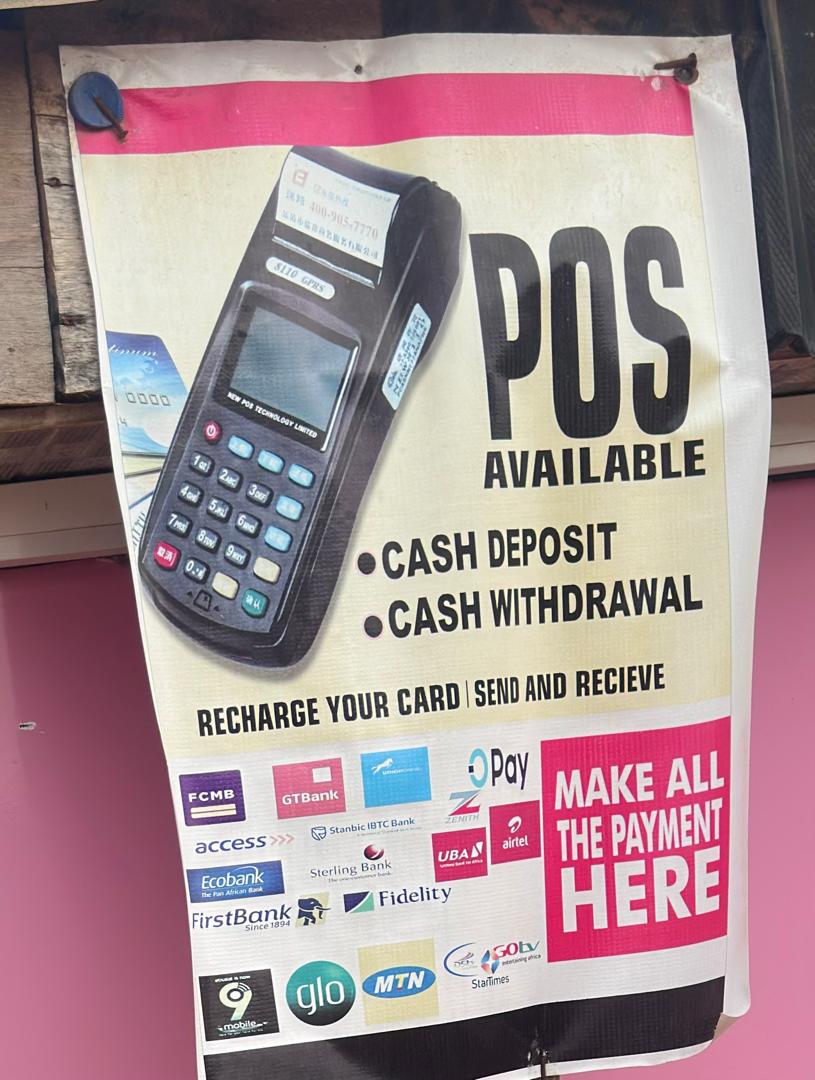

For this segment of the population, Point-of-Sale (POS) agents have emerged as the most visible, everyday face of Nigeria’s Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI), bringing banking services directly into neighbourhoods and markets.

This report by Bilkis Abdulraheem Lawal examines how POS agents are filling critical gaps in access to banking services across Lagos State, and what their rapid growth reveals about both the strengths and vulnerabilities of Nigeria’s digital payment architecture.

Banking Beyond the Banking Hall

Over the past decade, POS operations have become an integral part of Nigeria’s financial ecosystem, with Lagos at the centre of this transformation. Enabled largely by advances in the country’s expanding digital payment rails, POS agents now provide essential services such as cash withdrawals, deposits and transfers, often within walking distance of customers’ homes or businesses.

At the heart of this system is interoperability, a core DPI principle. Platforms such the Unstructured Supplementary Service Data (USSD), the Nigeria Inter-Bank Settlement System (NIBSS) and identity databases managed by the National Identity Management Commission (NIMC), have made it possible for people to transact seamlessly across banks and networks.

For residents of communities with few or no bank branches, the impact has been significant and transformative.

Mrs Abosede Oluwa, a resident of Elepete Baba Adisa along Ibeju-Lekki axis, said POS agents have transformed how she accesses her money. “There is no bank in my community,” she explained. “Before POS operators came, I had to travel to Epe for any bank transaction, but I rarely do that now.”

According to her, the cost of visiting her bank can be as high as ₦3,500 in transport fares alone. “With POS operators on almost every street, I only pay a small service charge and get my cash easily. It saves me both time and money,” she added.

Mrs Bolanle Adio, a resident of Lakowe, also in the Ibeju-Lekki axis, shared a similar experience. She said travelling to her bank costs about ₦2,000, and traffic congestion. “The distance and traffic make it stressful,” she said. “POS operators are more convenient.”

However, she noted that network failures can sometimes be frustrating. “There are times when my account is debited, but the money does not reflect in the agent’s account. If that’s the only money you have, it can be very upsetting,” she said.

In Ori-Okuta, Ikorodu, Miss Kindness Ugochukwu said the main challenge is not transport costs but stress and urgency. “Getting to the bank from my area is difficult,” she said. “The long queues can be discouraging, especially when you need money urgently. That’s why I mostly use POS agents.”

For others POS services also provide an entry point into the formal financial system. Mrs. Mariam, a petty trader, said she does not operate a bank account.

“I keep my money at home,” she said. “When customers want to transfer money, they pay to the POS agent beside me, and the agent gives me cash.”

How POS Operations Fit into Nigeria’s DPI

POS operations are powered by the payment layer of Nigeria’s Digital Public Infrastructure, which enables multiple actors, banks, fintechs, agents, and customers to interact on shared rails.

At the core is interoperability. NIBSS provides the backbone that connects banks and financial institutions, enabling seamless transfers across different platforms. This allows POS operators to use a single terminal to serve customers from multiple banks.

Also, secure digital identity systems such as the Bank Verification Number (BVN) and National Identification Number (NIN), managed by NIMC, play a key role. These systems help verify the identities of both operators and customers, reduce fraud and build trust in digital transactions.

Regulation has further supported adoption

The Central Bank of Nigeria’s (CBN) cashless policy and related guidelines have encouraged electronic payments, while recent measures such as the geo-tagging of POS terminals aim to improve security and accountability.

Beyond convenience, POS networks have expanded financial inclusion by bringing basic banking services to rural and underserved communities, easing pressure on banking halls and extending the reach of financial services.

Technological advances, including mobile POS devices, QR codes and contactless payments, have also made transactions faster and safer, reducing the risks associated with cash handling.

Together, these elements reflect DPI’s goal: open, interoperable systems that extend public and private services to underserved populations.

Challenges on the Frontline

Despite their benefits, POS agents operate at the most fragile end of the digital infrastructure, where failures are felt immediately.

Emmanuella Anyawu, a POS operator in the Eleko community, said the difficulties can sometimes outweigh the gains. “Fake alerts are a major problem,” she said. “You receive a notification, but the money never enters your account. Network issues also affect sales.”

Omowunmi Owolabi, an operator in Ibeju-Lekki, identified mistaken transfers as another risk. “If you mistakenly transfer money to a wrong account and the person refuses to return it, retrieving that money is very stressful,” she said. “Sometimes you don’t get it back at all, and that becomes a loss.”

In Ikorodu, Taofeek Olarenwaju described POS business as “lucrative but highly risky”. He said accessing cash remains a major hurdle due to withdrawal limits. “The Central Bank policy limits withdrawals to ₦500,000 per week,” he said. “I now partner with traders and fuel stations to get cash.”

He attributed many fraud cases to negligence and advised fellow operators to be vigilant. “Always collect customers’ details, request proof of transfer and confirm alerts properly before releasing cash,” he said.

These challenges highlight a core DPI tension: while digital systems expand access, weaknesses in connectivity, dispute resolution, and fraud controls can undermine trust at the last mile.

Expert Perspectives

Financial experts say the rise of POS agents reflects broader progress in Nigeria’s digital payment landscape.

Mr Olu Akanmu, Executive-in-Residence at Lagos Business School, said Nigeria has made notable strides in going cashless.

Speaking during an interview on Channels Television, he noted increased investment in digital services and growing adoption among small businesses.

“Pay-by-transfer has become more common, even among street vendors and market women,” he said. “That’s real evidence on the streets of the progress we’ve made.”

Citing data from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), Akanmu noted that the financial services sector grew by about 15 per cent year-on-year in the first quarter of 2025, far outpacing overall GDP growth. “That kind of expansion is likely driven by increased financial inclusion and the widening of digital financial services,” he explained.

However, he cautioned that much work remains. Akanmu said to unlock Nigeria’s full economic potential, fintechs and banks must deliberately reach the unbanked, calling for stronger collaboration to serve marginalised communities.

Professor Khadijat Yahaya of the Department of Accounting, University of Ilorin, also described POS services as “bringing the banking system to the people”. She said they are often faster and more convenient than traditional bank transfers.

She called for stricter regulation of telecommunications providers to improve network reliability and reduce high data costs, noting that POS agents depend heavily on stable connectivity.

Experts further recommend strengthening digital infrastructure to curb fraud, especially fake alerts, and simplifying the process for reversing transfers made in error.

This report is produced under the DPI Africa Journalism Fellowship Programme of the Media Foundation for West Africa and Co-Develop